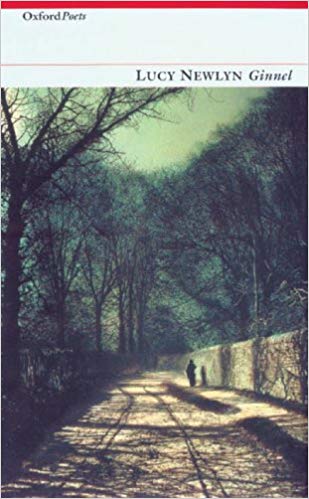

Ginnel

This closely unified sequence of poems is set in and around the ginnels of Leeds, where Lucy Newlyn grew up in the 1960s. Exploring the hinterlands of middle-class Headingley and working-class Meanwood, the sequence is pervaded by a sense of restlessness, of wandering between two worlds and times.

Ginnel (Oxford Poets, Carcanet, 2005)

'Ginnel' is the Northern dialect word for a passage between houses, and this closely unified sequence of poems is set in and around the ginnels of Leeds, where Lucy Newlyn grew up in the 1960s. Exploring the hinterlands of middle-class Headingley and working-class Meanwood, the sequence is pervaded by a sense of restlessness, of wandering between two worlds and times. Poems are constantly on the move, revisiting the places of childhood and childhood as a place. With acute particularity, they recall familiar sights and sounds, local people, favourite walks, dialect words learnt when playing out in the back streets. Just as ginnels intimately criss-cross the geographical terrain of Leeds, so they track the deepening of consciousness. This is poetry of firm local attachment, overlaid by a child's developing awareness of class divisions, separation, mortality and loss. The adult looks back, with a sense of exile.

Reviews

Sarah Crown in The Guardian

In the dialect of Lucy Newlyn's native Yorkshire, a ginnel is a narrow lane running between houses. Her debut collection carries us back in time to the ginnels of her childhood, describing in warmly observed detail the remembered geography of a world of "molten chocolate" conkers and days "battle-scarred" with brambling, where the bleakly northern "beating wind" and "cloud massed on hills" are a source of nostalgic delight. Initially, her poems deal in fundamentals - "Home", "Light", "Washing day" - a child's unshakeable realities, reinforced by precise, uncomplicated rhymes. As the collection moves on, however, earlier certainties begin to unravel. Her house, which looks out at the front over the "cherries and acacias" of Headingley and at the back on to "smog blackened" Meanwood, becomes liminal, and begins to symbolise the complexities and divisions she discovers in her growing self. In "The attic", from which "both worlds are visible", she feels "our lives tilting / across the join". But the frequency with which Newlyn moves between these worlds highlights the impassability of the threshold between then and now that is the real focus of her poems. The poignant sense of her exile from her own youth underpins a fine collection.

Interview with the Yorkshire Post

Selected Poems from Ginnel

Ginnel

You lost your French roots

long ago: came north, toughened

your grain. Liked it here, settled in;

never went south again – never

went further, if you could help it,

than the end of Yorkshire.

You fitted the place – not as a word

finds a thing, but as a thing finds

a word – becoming, in time, yourself.

Was it the matt templates of grey,

the stone walls against grey sky, light

scarce and edging across cobbles?

Was it the way cloud massed

on hills, wind hammered fells, bent

bracken, rocked dry-stone walls?

Was it the houses huddled

in the wind’s grip, wind raking the beck,

leaves driven in hordes against houses?

You thinned down, like an eel,

bending your body like a beck

between houses. You branched out,

sending fine veins toward the fells,

covering the land with cracks,

as a river crumples a map with fissures.

They’d not know you in middle England,

your looks are so altered. The sun

tips shadows over your high edges;

wind pelts you with detritus. You are

long and stony and grained. Footfalls

reverberate, lost in your still chambers.

Walls

I love the curt sounds of the vowels –

the way they hold back and stay put

like through-stones in wind-bitten walls:

’appen, mucky, luv, thissen, mek, nowt.

The consonants sturdy as footings

or knobbly as topstones, with a shut

sound – taffled, snicket, sneck, tekken –

to keep the sheep in and the gales out.

All the words rough and showing

their edges, with glottal stops as packers:

Ah s’ll be dahn on mi nogs ower lang

bah missen in t’ claggy muck and watter.

And the whole fabric holding together

without mortar against age and weather.

Juan taught me

What to do with chewing gum,

where to go for gob-stoppers,

how to un-clog a sherbet-fountain,

which tree had the best conkers;

how the street’s camber steers

a marble, when to treble-load a cap-gun,

how broken glass can start a fire,

the exact angle for ignition;

the non-existence of Father Christmas,

how to knot a conker-string,

when I should mind my own business,

why nettles don’t always sting;

the short-cuts at the back of Bentley

lane and Meanwood, why it was odd

not to live with my granny

go to church or believe in God;

the way to coax grubs into a jam-jar,

whether to pickle, drown, or grill them;

how to adorn cement and molten tar,

leaving my initials in them;

how to catch a louse and crack

its carapace, short vowels and the ‘f’ word,

how to spin a stone along the beck

and aim an air-gun at a blackbird;

what old tyres are for, making

a bike rear on its hind wheel,

taking angles, sudden braking,

how to smoke and hide the smell;

to wish I was a boy and working class;

not how to thank him, or bring back his face.

The bend

As we filed down the ginnel, turned the bend

and broke into a run

we knew who'd be first to reach the end.

Every Sunday the same: mum would send

us out in the morning sun.

As we filed down the ginnel and turned the bend

you were laughing. I could touch your hand

as you broke into a run.

We knew who’d be first to reach the end.

I was always there with you, one step behind

your shadow in the sun

as we filed down the ginnel and turned the bend,

your laughter carried away by the wind

as you broke into a run.

We knew you’d be first to reach the end

as we filed down the ginnel, and turned the bend.